Heroes in Fine Print

By Freddie Wilkinson, reprinted with permission. Originally published at Hardwear Sessions.

“On the mountain there were no heroes,” K2 survivor Cas van de Gevel was recently quoted as saying in Outside magazine, “just an unspoken agreement that you help as much as you can.”

Outside and Men’s Journal recently published feature-length pieces on the K2 disaster. Both stories lead with the tale of three European men, Wilco van Rooijen, Gerard McDonnell, and Marco Confortola, who bivouaced at nearly 28,000 feet after the catastrophic serac avalanche stripped the Bottleneck Couloir of its fixed ropes on the evening of August 1. The next day, they were forced to downclimb the Bottleneck unroped. Along the way they passed a party of distressed Korean climbers; the three abandoned them to continue their own descents to safety. Two of them made it, but McDonnell was swept to his death in an avalanche.

While Confortola and van Rooijen can hardly be faulted for not doing more, it does seem like their teammate Cas van de Gevel is right—the tragedy was a grim game of Russian roulette. It was every man for himself.

Yet some extraordinary acts of bravery and selflessness did occur on K2—you just might have to read the fine print to hear about it.

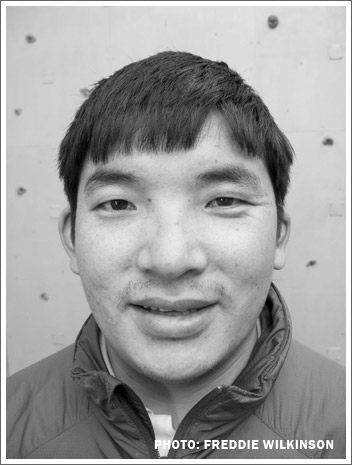

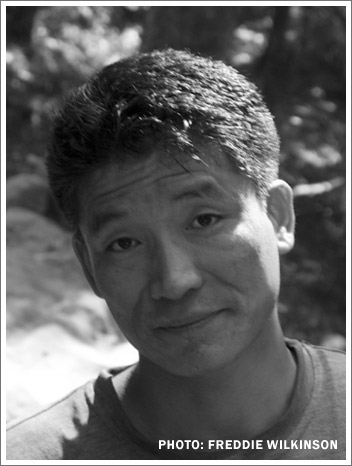

On a recent trip to Nepal, I tracked down two Sherpas, Chhiring Dorje and Pemba Gyalje, who were among those who summited on that fateful day. I had corresponded with them both via email for my own article in Rock and Ice, and I felt drawn to meet them in the flesh.

Pemba and Chhiring reached the summit at approximately 6:35 and 6:37 p.m. on August 1, making history by becoming the first two Sherpas to summit K2 without oxygen. But that’s not what makes them exceptional.

On the descent, at least seven climbers chose to bivouac rather than continue down in the darkness. Chhiring, the owner of Kathmandu-based Rolwaling Excursions guide service, continued. When he reached the Bottleneck, he discovered the ropes were missing. Small pieces of ice continually poured down the narrow gully from the serac above. He knew it could release another catastrophic avalanche at anytime. It was imperative to get out of harm’s way as quickly as possible. But another Sherpa guide had dropped his ice axe, effectively stranding him, so Chhiring tied him to his harness and downclimbed the couloir with his friend hanging off him. This was at 27,000 feet, in the middle of the night, after he had just summited K2 without oxygen.

Pemba Gyalje also downclimbed the Bottleneck that night. The next morning, he went out searching for his teammates van Rooijen and McDonnell. After returning to Camp IV unsuccessfully, he went out again, and eventually found Confortola passed out in the snow. As he revived him with oxygen, they were hit by another serac avalanche. Pemba held on to the helpless Confortola, saving him from being swept away with the slide. Then he walked him back to Camp IV, and, rather than rest, descended by headlamp to Camp III, where he rescued his partner van Rooijen the next morning.

After meeting the two Sherpas, it was clear that both men are far too humble to consider what they did that extraordinary. Nevertheless, the National Geographic Society chose to honor Pemba’s heroism by naming him its Adventurer of the Year. That’s him on the cover of this month’s National Geographic Adventure magazine. It’s good to see home-grown Himalayan guides getting that kind of

international recognition—all too often they labor in obscurity.

So, here is a good look at what two heroes look like:

7 comments

Comments feed for this article

December 7, 2008 at 7:14 am

Ralph Tingey

Freddy, Thanks for the great story!!! It was the best thing I’ve read about the mountains all year.

December 8, 2008 at 4:56 pm

Seth Hobby

Very Nice Freddy! By far an amazing effort of heroism on both Chirring and Pemba’s part. Thank you for sharing the story. So often the Sherpas are overlooked for their amazing effort and selflessness. I appreciate the reporting on your part.

January 15, 2009 at 11:34 pm

Jane Climber

We have read too many stories such as “Tomaz Humar and a porter reached the base camp at 5800 meters. Then Humar made a solo climb of Annapunrna…” as if the porter is not a human being but self-propelled load-carrier and an automatic belay device.

http://www.mounteverest.net/news.php?id=16750

Finally the NG walked out of the condescending colonial past and gave the true hero his proper place! Cover!

January 19, 2009 at 4:16 am

Kremer

Awesome Freddy… it’s like….. ” The rest of the story”. You should do radio , too.

April 1, 2009 at 1:07 am

Fred

Well-deserved kudos to Chhiring and Pemba!

Jane Climber, it’s true there are too many stories that ignore the contributions of Sherpas and porters. But the story you referenced about Tomas Humar didn’t seem to be one of those. The narrative of the climb began with “I start out with my friend Jagat Limbu. We cross the glacier ….” No reference to self-propelled belay devices.

April 1, 2009 at 9:12 pm

Steve Knowlton

Thanks Freddie! Great story and recognition long overdue!

July 21, 2009 at 4:30 pm

MichaellaS

tks for the effort you put in here I appreciate it!